- Jacob Faber, and edited by Anna Sucsy

- February 2021

- Fast Focus Research/Policy Brief No. 51-2021

Why do we care about whether government policies contributed to racial segregation?

Residential segregation is a strong predictor of educational and economic opportunity.[1] Americans living in majority Black and Brown neighborhoods are less likely to be employed in high-wage jobs, have access to credit, or score highly on standardized tests compared to Americans who live in predominantly White neighborhoods.[2] The persistence of high levels of Black/White residential segregation is increasingly seen as a problem for communities and the nation. In “We Built This: Consequences of New Deal Era Intervention in America’s Racial Geography” (2020), Jacob Faber explores the historical causes of residential segregation, concluding that federal housing policies implemented during the New Deal increased residential segregation by institutionalizing the idea that proximity to people of color decreases property values.[3]

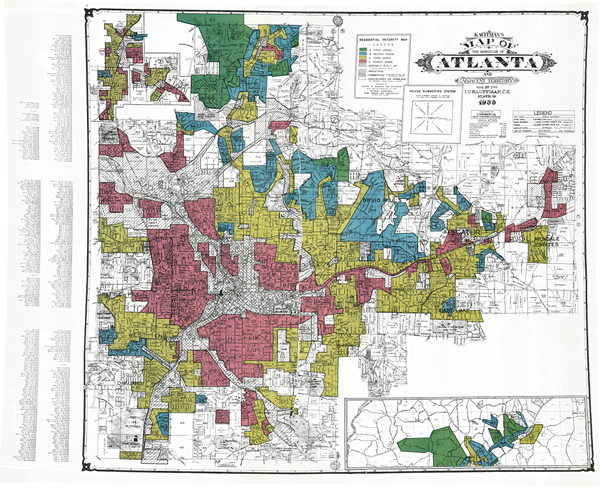

To better understand the long-term impacts of federal housing policy during the New Deal, Faber analyzed 100 years of census data to track racial geography over time in cities that were and were not appraised by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) (see text box). Referred to as “redlining” because neighborhoods with Black residents were deemed the least desirable and outlined in red, HOLC appraisals severely limited Black home-owners’ access to mortgage credit and home equity growth. Faber found that:

- Cities and towns appraised by HOLC became more segregated than cities and towns that were never appraised;

- HOLC’s exclusion of people and communities of color from affordable mortgage credit laid the foundation for the racial wealth gap; and

- HOLC’s legacy was cemented by the adoption of its policies by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and GI Bill, causing the consequences of appraisals to last longer than they would have absent their adoption by these programs.

Because HOLC guidelines determining which geographies to evaluate were not perfectly implemented, Faber was able to compare long-term outcomes for similarly sized cities based on whether they were ever appraised by HOLC.[5]

Cities that were appraised by HOLC are more racially segregated today than cities that were not appraised.

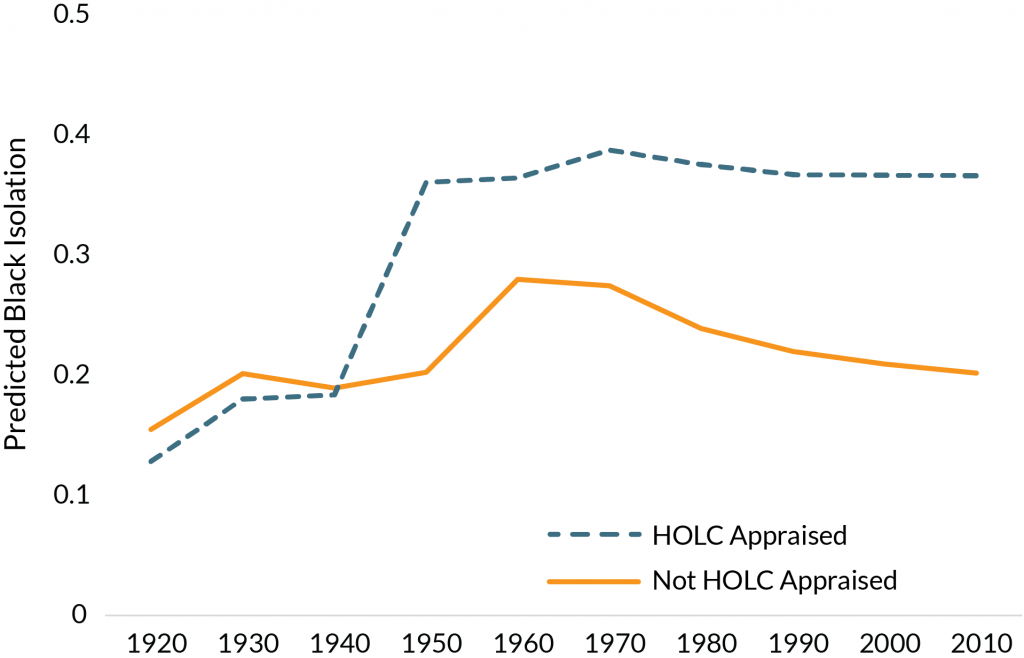

Faber found that cities that were not appraised by HOLC had similar levels of segregation in 2010 as they did in 1930, whereas appraised cities were more racially segregated in 2010 than in 1930. Faber measures racial segregation by “Black isolation.” Black isolation measures the likelihood of a Black resident living in a predominantly Black neighborhood. The Black isolation measure suggests that, in 2010, Black residents of appraised cities lived in neighborhoods that had, on average, a 16.4 percent higher share of Black residents compared to Black residents of unappraised cities (see Figure 1).

Faber found that the gaps that emerged in the 1940s between appraised and non-appraised cities have not closed in the intervening six decades.

Note: Rates of Black isolation in appraised and unappraised cities diverge statistically in 1970 and remain different through 2010.

Source: Faber, J. W. (2020). We Built This: Consequences of New Deal Era Intervention in America’s Racial Geography. American Sociological Review, 85(5), 739–775.

Redlining tied to the HOLC appraisals laid the foundation for the racial wealth gap.

Although New Deal housing programs did not invent segregationist mortgage provision, they institutionalized the practice, and implemented it at an unprecedented scale. These policies restricted Black families’ access to capital while increasing that of White families. Homeownership, inheritance of a house, and home equity are key ways that families accumulate assets and they remain some of the most powerful structural determinants of racial stratification.[6] By providing White families with access to low-cost mortgages and restricting Black families’ access, HOLC’s policies slowed Black families’ economic mobility.

The racial wealth gap impacts Black families and communities today.

- In 2010, the homeownership rate among White families was nearly double that of Black families.

- Historic exclusion from mortgage credit has made communities of color vulnerable to exploitation via severely constrained rental markets.[7]

- In 2013, the median White household had $13 in asset wealth for each $1 held by the median Black household.[8]

HOLC’s legacy of racial segregation was cemented by the adoption of its practices by subsequent federal policies, which exacerbated and lengthened its negative impacts.

Similar to HOLC, the FHA and GI Bill restricted housing assistance on the condition that prospective homeowners not buy homes in D-rated communities, which were deemed risky investments (see Text Box).[9] Because the presence of even one Black family could earn a neighborhood a “D” grade, this policy effectively restricted housing assistance to White Americans purchasing homes in White neighborhoods. The large scale of the FHA and GI Bill funding strengthened segregationist housing policies first institutionalized by HOLC; between 1950 and 1960, one third of privately-owned homes were financed by FHA or the GI Bill.[10] The GI Bill and the FHA abandoned explicitly racist policies after the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968. However, private appraisers continued to exclude communities of color from accessing mortgage credit, in part because of the institutionalization of the idea held by the federal government that proximity of people of color decreases property values. Faber asserts that had the FHA and GI Bill not adopted HOLC’s exclusionary policies, HOLC may not have had as strong or long-lasting impact on residential segregation as it did.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

Residential segregation is a strong predictor of economic and educational life outcomes.[11] Redlining tied to HOLC appraisals had significant effects on racial geography in the United States by formalizing and encouraging segregation through the drawing and grading of neighborhoods. The consequences of these policies continue today.

The longevity of the consequences of New Deal federal housing policies demonstrates that government interventions can have long-lasting impacts on residential segregation. A substantial investment in housing, similar to the investment that was made during the New Deal, with specifically anti-racist intentions may be a useful tool for policymakers in supporting residential desegregation and increasing equitable access to opportunity. Using inverted versions of HOLC’s original maps to guide contemporary investment (i.e. targeted investments in “D” grade neighborhoods) could be an additional step toward racial equity.

- Further exploration of the specific mechanisms though which HOLC implementation increased segregation;

- Further attention to regional differences in HOLC’s effects;

- Further examination of how community organizing may have played and continues to play a role in differentiating HOLC appraised cities from those that were not appraised.

Anna Sucsy is a Project Assistant at IRP and a Master of Public Affairs candidate at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Notes

[1]Chetty, R., Hendren N., Kline P., and Saez E. (2014). Where Is the Land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 129(4):1553–623. Sharkey, P., & Faber, J. W. (2014). Where, When, Why, and For Whom Do Residential Contexts Matter? Moving Away from the Dichotomous Understanding of Neighborhood Effects. Annual Review of Sociology, 40(1), 559–579.

[2]Faber, J. W. (2018). Segregation and the Geography of Creditworthiness: Racial Inequality in a Recovered Mortgage Market. Housing Policy Debate, 28(2), 215–247. Hwang, J., Hankinson, M., & Brown, K. S. (2015). Racial and Spatial Targeting: Segregation and Subprime Lending Within and Across Metropolitan Areas. Social Forces, 93(3), 1081–1108. Hyra, D., Squires G., Renner R., and Kirk D. (2013). Metropolitan Segregation and the Subprime Lending Crisis. Housing Policy Debate 23(1):37–41. Reardon, S. F., Kalogrides, D., & Shores, K. (2019). The Geography of Racial/Ethnic Test Score Gaps. American Journal of Sociology, 124(4), 1164–1221. Steil, J., De la Roca, J., & Ellen I. G. (2015). Desvinculado y Desigual: Is Segregation Harmful to Latinos? ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 660(1): 57–76.

[3]Faber, J. W. (2020). We Built This: Consequences of New Deal Era Intervention in America’s Racial Geography. American Sociological Review 85(5): 739–775.

[4]Mitchell, B. & Franco, J. (2018). HOLC “Redlining” Maps: The Persistent Structure of Segregation and Economic Inequality. National Community Reinvestment Coalition.

[5]Federal guidelines requested HOLC appraisals of all cities with populations above 40,000, but some cities with populations above 40,000 were never appraised. Faber assumes that changes in segregation after 1930 would have been the same for appraised and non-appraised cities absent HOLC implementation.

[6]Desmond, M. (2017). How Homeownership Became the Engine of American Inequality. The New York Times Magazine. Faber, J. & Ellen. I. G. (2016). Race and the Housing Cycle: Differences in Home Equity Trends Among Long-Term Homeowners. Housing Policy Debate 26(3):456–73. Massey, D. S. (2007). Categorically Unequal. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; Oliver, M. L., & Shapiro, T. (2006). Black Wealth, White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality. New York: Taylor & Francis.

[7]Connolly, N. (2014). A World More Concrete: Real Estate and the Remaking of Jim Crow South Florida. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

[8]Kochhar, R. & Fry, R. (2014). Wealth Inequality Has Widened Along Racial, Ethnic Lines Since End of Great Recession. Pew Research Center.

[9]HOLC issued loans from 1933 to 1936 and was implemented as a short-term solution to help homeowners avoid foreclosure and buy back homes lost during the Great Depression: see Courtemanche, C., & Snowden, K. (2011). Repairing a Mortgage Crisis: HOLC Lending and Its Impact on Local Housing Markets. The Journal of Economic History, 71(2), 307-337. Its segregationist policies were continued by the FHA (1934–present, now Department of Housing and Urban Development) and the GI Bill (1944–present): see HUD.Gov. (n.d.) The Federal Housing Administration; and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. (2013, November 21). History and Timeline. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 banned racial discrimination in mortgage provision: See Mitchell & Franco, HOLC “Redlining” Maps.

[10]Dreier, P., Mollenkopf, J., Swanstrom, T. (2005). Place Matters: Metropolitics for the Twenty-First Century. University Press of Kansas.

[11]Chetty, Hendren, Kline, and Saez. Where Is the Land of Opportunity?; Sharkey & Faber. Where, When, Why, and For Whom Do Residential Contexts Matter?

Categories

Economic Support, Financial Security, Housing, Housing Market, Inequality & Mobility, Neighborhood Effects, Place, Racial/Ethnic Inequality